Love, loss, and a Sacramento sprinter's fight to carry on

Through grief, a high school athlete found hope and purpose on the track

The cadences rang across the Inderkum High School track.

“Go!” Mahogany Stone shouted as she raced onto the blue rubber track of the baton exchange zone, a 20-meter stretch where championship hopes can end with a dropped or mistimed pass.

“Stick!” she yelled to teammate Nariyah Wilson while extending the aluminum baton.

Cebrina Lewis-Jackson has one of the fastest 4x100-meter relay teams in the Sacramento region. It’s just a matter of cleaning up their exchanges at an afternoon practice in late May, two days before the state meet in Clovis. The coach is prepared for the first scorching heat in northwest Sacramento, watching from the shade of her oversized black-and-white umbrella.

“Go! … Stick!”

A month earlier, Lewis-Jackson moved Myah Collier from the third leg of the relay to the opening leg. The senior struggled with pacing herself out of the starting blocks, especially when running in the outside lane with no competitors to chase after.

“Seven,” Myah grumbled when teammates asked about their lane assignment for state qualifying. “Lane 7,” she assured them of her worst-case scenario, all six competitors at her heels. “When I feel I’m going to fall forward,” Myah explained of her race strategy, “I know I’m going fast enough.”

The girls recently broke 48 seconds for the first time in school history at the Section Masters. Jazzmin Williams held off St. Mary’s High of Stockton in the last leg for the final qualifying spot in the state meet.

But this team is no longer defined by speed alone. Days before the biggest race of the season, the only time that truly mattered was the present.

They had found their purpose in lifting a senior leader through her darkest days. Her heart was broken. Her family was devastated. Yet, somehow, love prevailed.

Born into speed

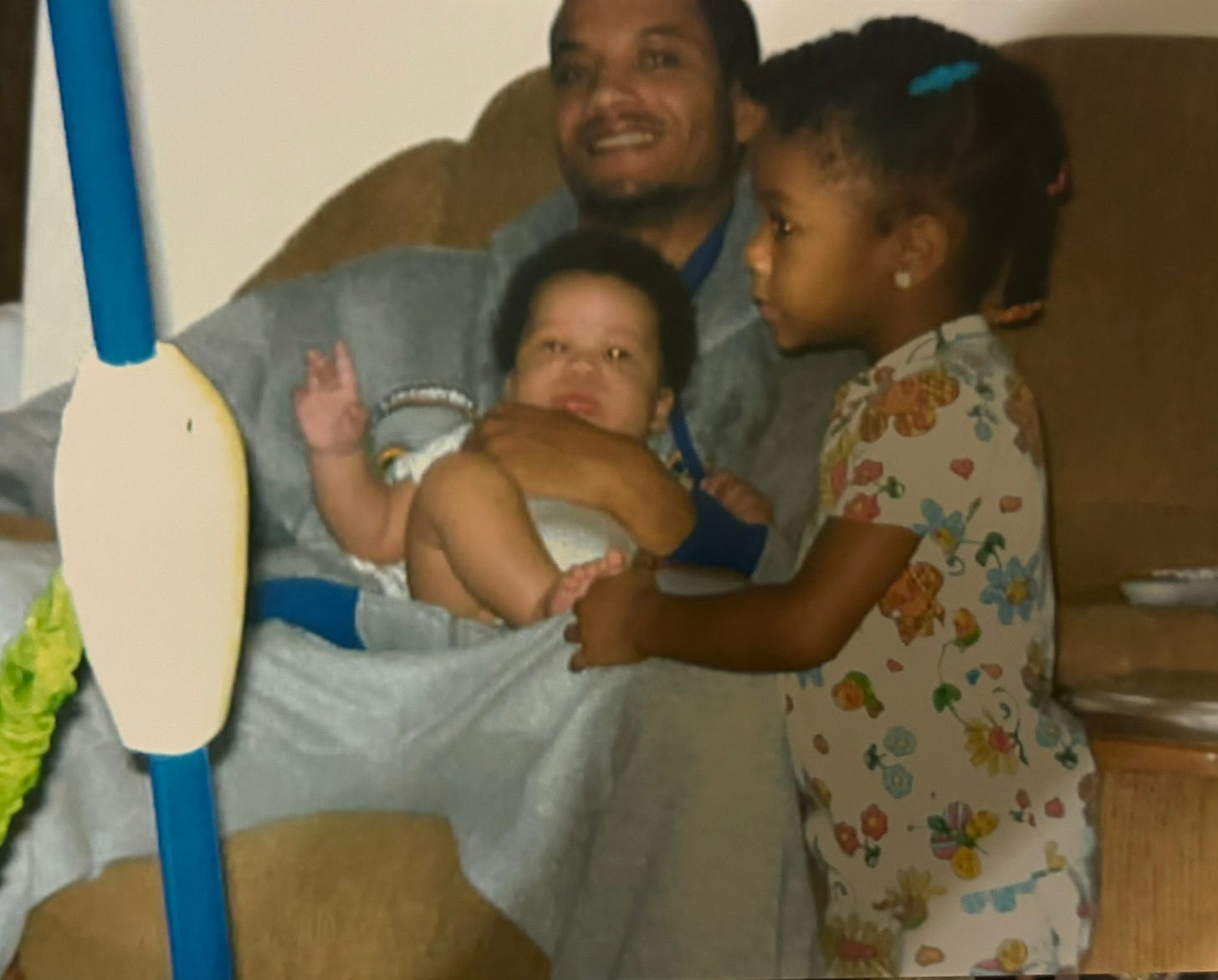

Jonathan Stone and Phonecia Holly met in 1994 at a high school track meet in the Bay Area. Jonathan was a football standout from San Jose. Phonecia had moved from Mississippi to Salinas at age 7 with her mother and sister. The teenagers fell in love.

One summer evening in 1997, Jonathan drove to Salinas for a date. The couple rode the carousel at a fair. On their way home, a weary Jonathan nearly drove off the road. Phonecia urged her boyfriend to spend the night. Instead, Jonathan drove to San Jose.

Jonathan fell asleep and slammed into the freeway sound barrier. The car flipped and Jonathan used his left arm to protect his face from dragging on the asphalt. He needed emergency surgery to save his hand, and another to salvage his football career.

The couple attended UC Davis. Phonecia ran the anchor leg on the 4x100 relay and bonded with teammates and coaches. Jonathan’s football abilities weren’t the same after the crash. He became a member of Phi Beta Sigma, one of the “Divine Nine” Black fraternities and sororities, and earned a degree in communications.

Jonathan and Phonecia married in 2003 — in July, specifically, so they would both be 25. Mahogany, the couple’s first child, was born in 2006. Their son was born in 2008.

A year later, Jonathan was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. The medication needed for his psychosis, as Jonathan understood it, would shorten his life.

The father poured his heart into his family. Jonathan took Mahogany to karate classes and volleyball matches. He attended his kids’ middle school graduations. The Stones traveled to a wedding in Mississippi, a reunion in Las Vegas and vacationed in New Orleans. Each New Year’s Eve, they cooked soul food and watched college football.

Jonathan loved talking about his football glory days, before the car crash. So much so that Phonecia and the kids called him “Uncle Rico,” after the character from the movie “Napoleon Dynamite” who swore he “could have thrown a pigskin a quarter mile.”

Phonecia says he was even better at basketball, a 3-point machine well before Stephen Curry.

Jonathan became a behavioral specialist, licensed to work with autistic children. To make extra money for the family, he drove for a ridesharing service. In his spare time, Jonathan made music he hoped would “plant good seeds that blossom good fruit.”

He would wake Mahogany in the early hours with his phone pointed at her confused, drowsy eyes. “My daughter says good morning,” he captioned those photographs on social media.

“He loved to take a good, candid picture,” Mahogany said.

But through this love, Jonathan struggled with his mental health.

In late April, Jonathan reached fraternity brothers with an “alarming” text message, friend Tony Trunnell said. Trunnell, a school psychologist, visited Jonathan at his home and the fraternity brothers spoke for a few hours. Trunnell knew Jonathan was in pain.

On April 28, Jonathan went missing.

A track family

The 4x100 relay team, at that time, seemed destined for the state championship.

After Myah rejoined the team after her basketball season, the girls ran under 49 seconds for the first time in school history at the Arcadia Invitational in Los Angeles. Mahogany, Jazzmin and Nariyah were each breaking 13 seconds in the 100 meters.

Inderkum had one of the fastest teams in Northern California — on paper, at least.

The girls struggled with their baton exchanges. They needed to trim another second off their time before the Section Masters to earn one of three spots in the state meet.

“I couldn’t understand why it wasn’t working,” Lewis-Jackson said of the handoffs. “Mahogany was a dynamic leader. She said, ‘We are going to get this.’ They always encouraged each other. There was never anything negative. If we have a mess up, just let it go.”

Head coach John Knowles never formally made Mahogany a captain, but her leadership position was understood.

“I believe captains appoint themselves,” he says.

After joining the Inderkum High track team as a sophomore, Mahogany quickly made varsity in the 4x100 relay, the event her mother excelled in decades earlier. She befriended Jazzmin, a freshman who had dominated junior meets.

“I taught her things about life,” Mahogany said. “She taught me about track.”

Lewis-Jackson fixed what she called a “roadrunner” start for Mahogany, where the sprinter chopped her first steps out of the blocks. Mahogany’s 100 time soon dropped below 13 seconds. She joined Sacramento Speed Factory, a summer program led by Knowles, where she trained through 100-degree heat and dazzled at weekend meets.

“Mahogany sets the tone for the team,” said Knowles, a Fairfield native who ran track at Sacramento State. “When it was time to be in conditioning, when it was time to lift, she was the first one there. She's not messing around.”

By Mahogany’s senior season, Knowles was setting practice around her warmups.

“Once she’s done,” he said, “the clock starts.”

The team was challenged each day at practice.

“Are you going to be participants or competitors?” Knowles would ask. “There are people who are here to be social. That’s cool, but stay out of the way of competitors.”

Shauna Jackson, Cebrina’s daughter, coached jumping events and brought “a little more attitude” to the Inderkum staff, said Mahogany, who enjoyed watching the mother-daughter dynamic. Shauna became more independent in her coaching as Cebrina gave her daughter the space she needed to grow.

Mell Frost, a middle distance coach at Sacramento Speed Factory, joined the high school staff before Mahogany’s senior season. “At first I thought she was standoffish,” Mahogany said of Frost, who moved to the Central Valley as a teenager to escape inner-city Los Angeles. “She’s so sweet, but she knows what she likes and what she doesn’t. She reminds me of some of my family members.”

Distance coach Gus Gonzales, an Inderkum graduate and substitute teacher at his alma mater, checked in with athletes during the day and lent an empathetic ear after meets. “Very shy and super quiet,” Mahogany said of the coach, “but once you get him talking he is so smart.”

During Mahogany’s sophomore and junior years, the 4x100 team narrowly missed the state meet. As a senior, Mahogany quit the cheerleading team to focus on track.

“She saw what I saw,” Phonecia said of her daughter’s passion for the sport. “That there was a different connection and community. I was glad she got that and fell in love with it as I did.”

At the Meet of Champions on April 20, a bad exchange led to a disqualification.

After that setback, Lewis-Jackson switched the relay order. She had been impressed with Mahogany’s burst in 200 meters, and moved the senior to the second leg. Nariyah moved from second leg to third leg; Myah third to first; and Jazzmin stayed the anchor.

“That changed the trajectory of where they were,” said Lewis-Jackson, who in 1994 reached the state meet in the 4x100 at Highlands High. “Once we had 48s (seconds), we had been dropping that time every week. I was like, ‘Oh, this, this is the group right here!’ ”

The relay team won their final league race in 48.86 seconds.

‘I knew I was loved’

After receiving a tip that Jonathan’s car was spotted in Elko, Nevada, a six-hour drive from Sacramento, the family planned to search for him over the first weekend in May.

“Logically, we were like, there is still a lot of racism around,” Mahogany remembers. “We wanted to make sure he was safe as a person. We didn’t want him to be a victim of anything out there.”

The Friday before the search, Mahogany was hopeful. She competed in the league championships at Bella Vista High School. Phonecia stayed home.

“We were just looking for something positive,” Lewis-Jackson said of the meet. “To see her go out there and shine for her dad.”

Mahogany won the 200 meters in 26.06 seconds and finished second to Jazzmin in the 100. After cheering teammates in the 4x400 relay, Mahogany returned to the stadium bleachers to grab her bag and check her phone. She had received a text from a cousin.

“Sorry for your loss,” it read.

“What do you mean, ‘loss’?” Mahogany thought. Looking back, she was in denial.

“Then, it clicked. My dad had been missing. I was more aware at that point.

“Let me call my mom,” she thought. “In my head, I was like, (my cousin) don’t know nothing.

“I called my mom. My voice cracked because I started to realize what was happening.”

Phonecia began crying instantly.

“At that point, I realized that my dad was gone.”

Mahogany threw her phone.

“Kids came running,” recalls Lewis-Jackson, who heard the screaming from the field. “ ‘Coach Cebrina, you need to get here fast.’ ”

Coach Frost held Mahogany from one side. Coach Knowles crouched from the other. When Lewis-Jackson arrived, Mahogany collapsed into her lap. The coach prayed.

“I knew she was heavenly in her faith,” Lewis-Jackson said. “Normally, we don’t mix God and school. But I knew who she was. She talked about (her faith) all the time. Her mom wasn’t there.

“I knew she needed some peace.”

Mahogany’s eyes went blurry. She was drained from all the crying and screaming.

“I couldn’t cry anymore,” she said. Parents moved kids away. Coaches lifted Mahogany to her feet. She hugged Rickey Green III, a friend and teammate. “I was protected.”

Jazzmin and Myah helped her down the bleachers and to the bus. “My legs are weak and I’m trying my hardest to stay upright,” Mahogany said. “They took their time. I knew they cared.”

Mahogany left her bags with Rickey and sat with Lewis-Jackson on the ride to Inderkum. The coach spoke of her own journey to faith. “She said, ‘God got me,” Mahogany remembers.

“I told my mom (over the phone), ‘I’m OK. My coaches and track family have me.

“I knew I was loved,” she said. “I knew my dad wasn’t in pain and fighting for his mind.”

A disparity in care

Mahogany hopes her family’s story can help kids whose parents struggle with mental health.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in 2020 that about 20 percent of American adults have a mental-health disorder. Black Americans are significantly more likely to report unmet needs in mental-health care and twice as likely to resort to emergency services for treatment.

The National Library of Medicine Study sheds light on what might create that disparity. In a survey of Americans receiving mental-health services, Black Americans reported unmet needs 10.2 percent of the time, compared to 5.1 percent of the general population. Top reasons included the cost of insurance, a minimization of symptoms and a distrust of government institutions.

Phonecia became frustrated by a system she believes failed the family as Jonathan’s condition grew worse. Remote therapy sessions during the coronavirus pandemic weren’t as effective. A family therapist, when learning Phonecia was a social worker, joked that maybe she could do a better job. The same therapist, who is white, made racial statements that angered the family and led to arguments. During Jonathan’s final months, Phonecia said his regular psychiatrist went on leave and the new psychiatrist would only prescribe medication after meeting him in person.

Mahogany watched her father struggle.

In January, she addressed a rise in suicide among Black Americans during a spoken-word performance for the talent portion of the Miss Black Teen Sacramento pageant. Mahogany won the competition, earning a college scholarship. A few months later, the Stones celebrated her acceptance to Jackson State, a historically Black college.

“I don’t understand how we pretend the world isn’t falling apart and nobody is doing anything to help,” Mahogany cried during the performance, with Jonathan and Phonecia in the audience. “It breaks my heart … and I don’t know what to do.”

A bill in the California assembly aims to close the racial disparities in mental health. AB 1970, authored by Assemblymember Corey A. Jackson (D-Moreno Valley), would develop training for a “Black Mental Health Navigator Certification” program.

“Certification equates to professionalism,” said Dominique Paxton of the California Black Women’s Health Project, in support of the bill at a June hearing at the Capitol. “Certification for our community in particular is a testament to the recognition that culture, heritage, history and race are social determinants of health and wellness.”

Hope and purpose

After Jonathan’s death, the Inderkum track family stayed by Mahogany’s side.

“They’ve been the ones keeping me here and keeping me motivated to know that, at the end of the day, my life didn't end,” she said after practicing baton exchanges with Nariyah. “So I gotta keep pushing. And (my dad) would be so proud.

“At first, everything was telling me to quit. Just, no. Stop. But by the time I got to the bus, my whole mindset changed. I was telling myself, just because my dad isn’t with us doesn’t mean our lives stop.”

With encouragement from Phonecia, Mahogany went to prom the night after learning of her father’s death. She returned to practice Monday, with state qualifiers days away.

“I wasn’t a coach anymore,” Lewis-Jackson said. “The mother in me took over.”

The Sac-Joaquin Section Division II meet on May 8 was also held at Bella Vista High, which brought back “a lot of anger and frustration,” Mahogany said.

“There will be times where you’re really frustrated and you want to cry,” coaches told her. “If you hold it in it will make for a problem, but if you get it out when you’re feeling it, you will feel a lot better.”’

Mahogany posted a personal-record time of 12.27 seconds in the 100 meters, and another personal record of 25.31 in the 200. The 4x100 team clocked 48.46 in the finals to again break the school record. Mahogany qualified for the Section Masters in all three events.

Throughout the qualifying meets, she felt signs of her father. There was the gust of wind that struck Mahogany on the starting blocks before one race. Before another race, she saw a man who looked like Jonathan. “He was here and saying hello,” she says. “Making sure I was going to be alright.”

Jonathan’s parents attended the Section Masters in Davis on May 18, where the top three finishers would advance to the state meet. Mahogany was eliminated in the 100 and 200 preliminaries, but the 4x100 team advanced to finals in 47.96 seconds.

But exchange issues between Mahogany and Nariyah lingered. Sometimes Nariyah began running too soon and left the exchange zone before receiving the baton. Earlier in the season, the team began shouting “Go!” when they entered the exchange zone, in addition to “Stick!” when they extended the baton. Mahogany and Nariyah walked the track before each race. But Mahogany doesn’t recall nerves before the Masters final.

“I realized, what’s in the cards is in the cards,” she said. “It was a peaceful moment. This is one of the last times I will step on the track as a high schooler.”

Mahogany thought about her father. Her mother was in the crowd.

Myah, starting in Lane 5, was in the middle of the eight-team pack when she passed the baton to Mahogany. Mahogany made up ground in the second leg and handed to Nariyah a half step before she left the exchange zone. “It was a little hiccup,” Mahogany recalls, “but she got out and ran amazing.”

Nariyah was in fourth place when she handed to Jazzmin, who accelerated past St. Mary’s High to jump into third. With cowbells clanging and coaches screaming, the fastest girl at Inderkum High held on to the last qualifying spot for the state meet.

“It was neck-and-neck down stretch,” Lewis-Jackson recalls. “When we got the last baton exchange, I knew we were in. As soon as they finished, I was on the field. Smiles were ear to ear. They accomplished what they set out to do.”

‘A genuine brother’

Two months have passed since Jonathan’s death. Phonecia and Mahogany attend a Sacramento Speed Factory practice — another chance to thank Knowles and Frost.

Pride and melancholy wash over the coaches as Mahogany and Phonecia hold a Jackson State sweatshirt. The blue-and-white hoodie is too hot to wear on this June afternoon in Sacramento, but it will be perfect for autumn evenings in Mississippi.

“I always get emotional when talking about Mahogany,” says Frost, who teases her sprinter about not calling enough. “She was supposed to be my forever kid.”

Phonecia didn’t attend the state championships in Clovis. Jonathan’s viewing was Saturday of the meet. Mahogany told her mother to stay in Sacramento.

The 4x100 team ran 48.89 seconds in preliminaries and missed the finals. Rickey, who held the fastest 110-meter hurdles time in California, missed his finals by one spot.

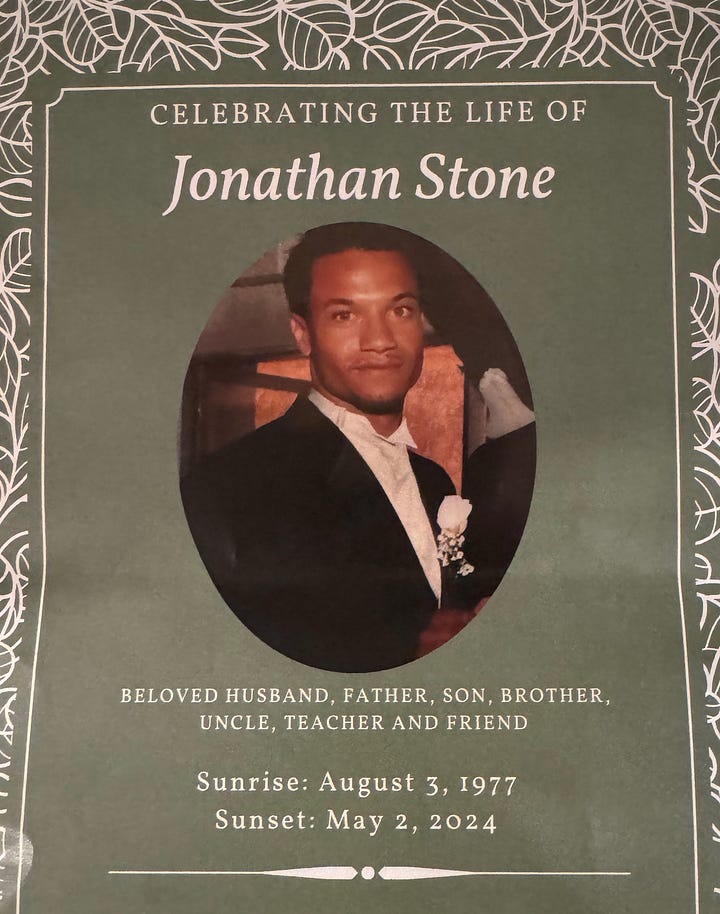

A few days after the meet, a celebration of Jonathan’s life was held at Parkway Church of Christ in Sacramento. Fraternity brothers sang a hymn and formed a crescent around the casket.

“I think people were in disbelief,” said Trunnell, who spoke about his fraternity brother at the service. “He had a nice heart. A genuine brother. People were abreast of what happened. There was a sense of uncertainty. You would think, I got my family, house, kids, parents. And then you think, is that enough? You never know.”

Phonecia hasn’t left the house much. She took leave from work. Her family made a surprise visit on her birthday. Most days have been spent cleaning and organizing, preparing to move into a more affordable apartment across town.

When she was Mahogany’s age, Phonecia dreamt of attending Jackson State — spending time with her Mississippi family, maybe getting selected by a sorority.

Mahogany will leave for the fall semester in August. She plans to try out for the university track team, perhaps joining Rickey, who has been offered a scholarship.

“I don’t want her to go,” Phonecia said, “but I do want her to be great.”

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or go to Speakingofsuicide.com/resources/ for a list of additional resources.