Oakland's Golf Guru: Banned because of race, WWII vet groomed champs at local range

PGA bylaws barred Black players and teachers up to 1961, so Lucious Bateman taught at Airway Fairways driving range near the Oakland Airport, where he groomed PGA players and a British Open champion.

What everyone can agree on is that Black golfing pioneer Charlie Sifford still owes $5 to Lucious Bateman. Beyond that, like with Babe Ruth’s called shot or Michael Jordan’s flu game, the story is told with different levels of absurdity.

Let’s go with three-time PGA winner Dick Lotz’s version.

“Now stories get inflated,” Lotz warns, “but the story that I heard from Loosh was he and Charlie played match play. Charlie came up to Northern California with a financier who was taking odds. Lucius was a very good player. After nine holes (at Alameda muni), Charlie went to the bathroom. And they waited and waited and waited … and he never came out.

“He had climbed out the back window.”

Years later, Lotz said he approached Sifford about the story.

“Never heard of the guy,” Sifford said.

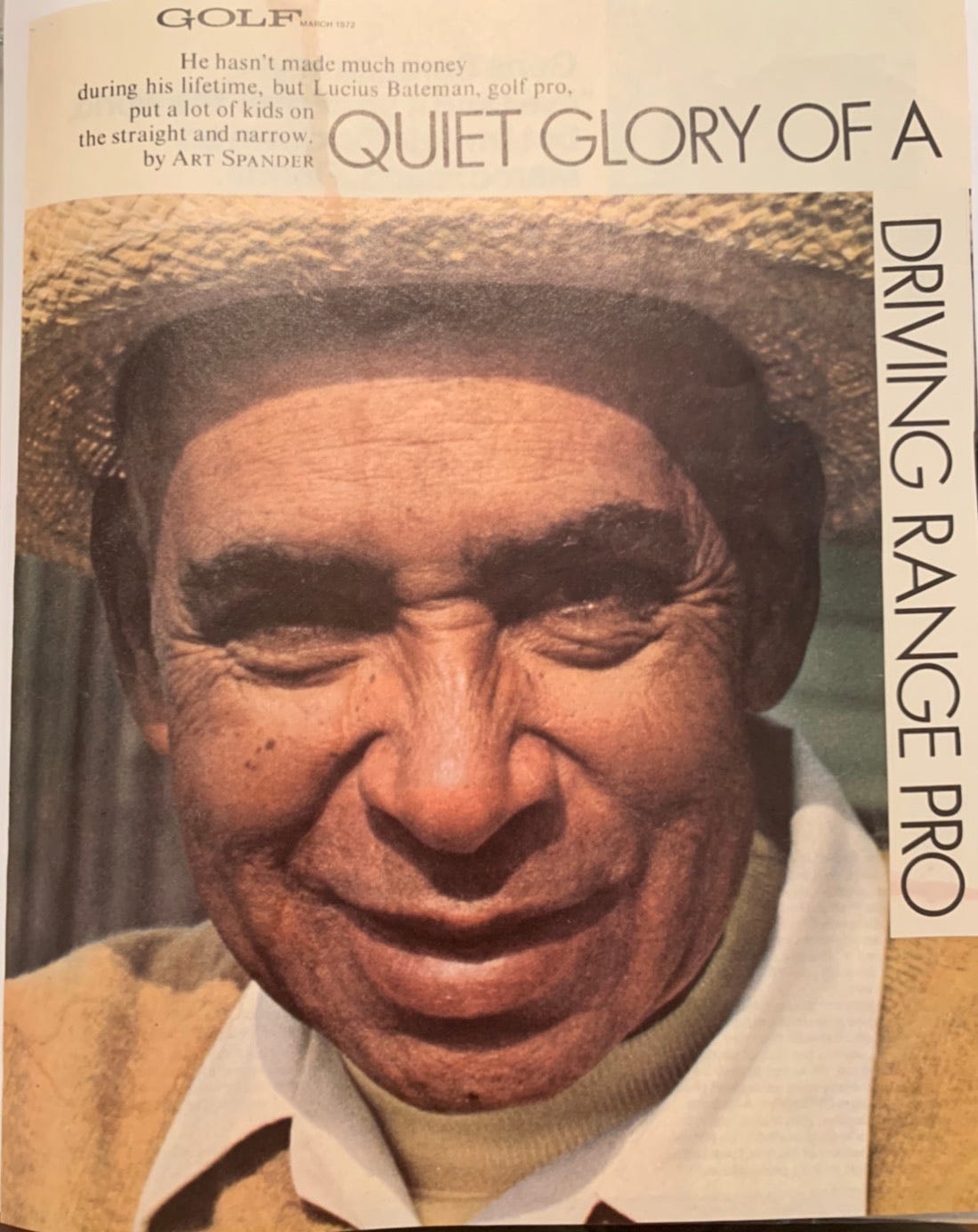

Lotz, like many East Bay kids in the 1950s and 60s, learned from Bateman, a Black man stripped of a PGA career because of the governing body’s Caucasians-only clause. Bateman served as a maintenance man and instructor at Airway Fairways driving range near the Oakland Airport, where he paid kids 90 cents to shag balls. In return, the Bateman Boys hit range balls for free and picked up golf tips and life lessons. The most famous Bateman Boy was “Champagne” Tony Lema, who won the 1964 British Open before dying in a plane crash two years later.

“Many kids might have made jails instead of pars and birdies if it hadn’t been for Loosh,” Lema said in a 1965 Golf Digest article about Bateman.

Born in 1906, Bateman picked up the game as a caddie in Biloxi, Mississippi, while his mother worked in the fields. He held the course record at Edgewater Country Club as a teenager and taught the game to its members. After serving in the Air Force during WWII, Bateman settled in Oakland and worked in the Alameda shipyards. The golf hustler, who stood 6-foot and typically wore a cap and sweater, set course records across the Bay Area. His passion, however, was working under Rig Ballard at a rundown driving range.

“First range pick was around 5 p.m.,” says Gary Plato, a Bateman Boy turned PGA teaching pro. “At 7 p.m. we did homework. Final pick was at 9. We’d dump 5-gallon buckets of golf balls in wheelbarrows, take those in and wash them — fresh balls were double-striped, slightly worn balls got a red stripe, the lowest grade got blue stripes. Ballard got a lot of mileage out of those balls.”

Randy Herzberg, who “was almost a sidekick” to the instructor, never knew Bateman to be in a relationship. Perhaps that stemmed from a traumatic upbringing as a Black boy in the South. “He did tell me one time that he saw one of his best friends hanged for being with a white woman,” said Herzberg, now an instructor at Corica Park in Alameda.

Bateman lived with his sister in a house on 77th Avenue in Oakland. Golf balls from his aces sat in ash trays. He made his living hustling on local courses and giving up to 30 lessons per day, at $3 a pop. On Fridays, he would pick up the Bateman Boys from Alameda High School and take them to golf courses across the region. Bateman became frustrated with his inability to get more Black kids involved with the game.

When the PGA’s discriminatory clause was repealed in 1961, long after Bateman’s playing hopes had passed, golf clubs requested Bateman as a teaching pro. He stayed at the range.

Lotz, like Lema before him, played money games with Bateman at Lake Chabot GC in the Oakland hills. He traveled with Bateman to Southern California for mixed events with Black players who, unlike Lotz who is white, were denied PGA access.

“Bateman and I, we didn’t play for too much money,” Lotz said. “A dollar or 50 cents. And when you made a bad decision, he made a story of it. ‘Oh, you short-sided yourself! Oh, you made a bogey out of a birdie putt!’

Above all, Bateman stressed short game practice and a compact swing.

“Bateman said you need to know your pin placements. Whenever you’re walking a course and see a green that you’ll play later in the day, look at the pin placement and memorize it. And know what angle you want to approach it.

“He took us to the green and said, ‘Look back to the tee box, and that will tell you what to do from the tee; whether to hit a draw or a fade. What side of the tee box to tee up on — go to the right side for a fade, left side for a draw.’

“One day he was sitting there watching me,” Lotz said, “and would you guess who was next to him? Tony Lema. Tony says, ‘Mind if I say something?’ Loosh said, ‘No, go ahead.’

“Lema helped square up my alignment. ‘That will get you good ball position.’ That was right after he won the Open.”

On the shores of the San Francisco Bay, where Bateman Boys once searched drainage ditches for golf balls, now sits a Hilton airport hotel. Airway Fairways closed in the late 60s and Bateman died in 1972, leaving a legacy of PGA golfers and teaching pros -- a legacy he was barred from forging himself. Bateman became an honorary member of the Northern California PGA in 2009, thanks to the efforts of Plato and other Bateman Boys.

“With race in front of everybody over the years, I have never seen a person handle it better than Lucius Bateman,” said Plato, who entered his lone PGA event with Bateman’s money — “he handed me two twenties and a ten.”

“He taught us a lot of how to handle adversity and curve balls that come your way. My admiration for Lucius grew stronger every year.”

Note: A previous version spelled Lucious name incorrectly.

Nick Lozito is a freelance writer. Follow him on Twitter at @NickHLozito or contact by email at nlozito2@gmail.com.

We need a book about the great Lucius Bateman! It's a great story and it needs to be told. I would hope that a reporter could follow up on this!

I once played with Lucious as a young 13 year old boy from Oakland in 1963. He was coaching 2 younger boys who had great Wilson Staff clubs and me with my hickory shaft clubs from the Good Will store. Lucious was kind, quite and had a limp. I just remember him hitting a 3 iron about 200 yds stiff on the pin. I said to myself, who is this guy?

I now know Iwas playing with greatness and class. I soaked up a lot about golf and life that day.

Art Watkins