Why Napa? How a North Bay course and Oakland company lured the PGA, and its stars

With PGA of America seeking a Bay Area stronghold, a famed amateur sealed deal

Max Homa is in Napa this week eyeing a third consecutive victory at Silverado Country Club. On the practice green Tuesday, back from a Rome scouting trip with Justin Thomas and his Ryder Cup teammates, the Cal alum enlightened competitors on Marco Simone golf course.

Thomas comes to Silverado hoping to rekindle the playing form that once took him to No. 1 in the world, but has eluded him in recent months and may have nearly cost him a Ryder Cup pick. Caddie Jim “Bones” Mackay kept a close eye on Thomas as he drilled home short putts.

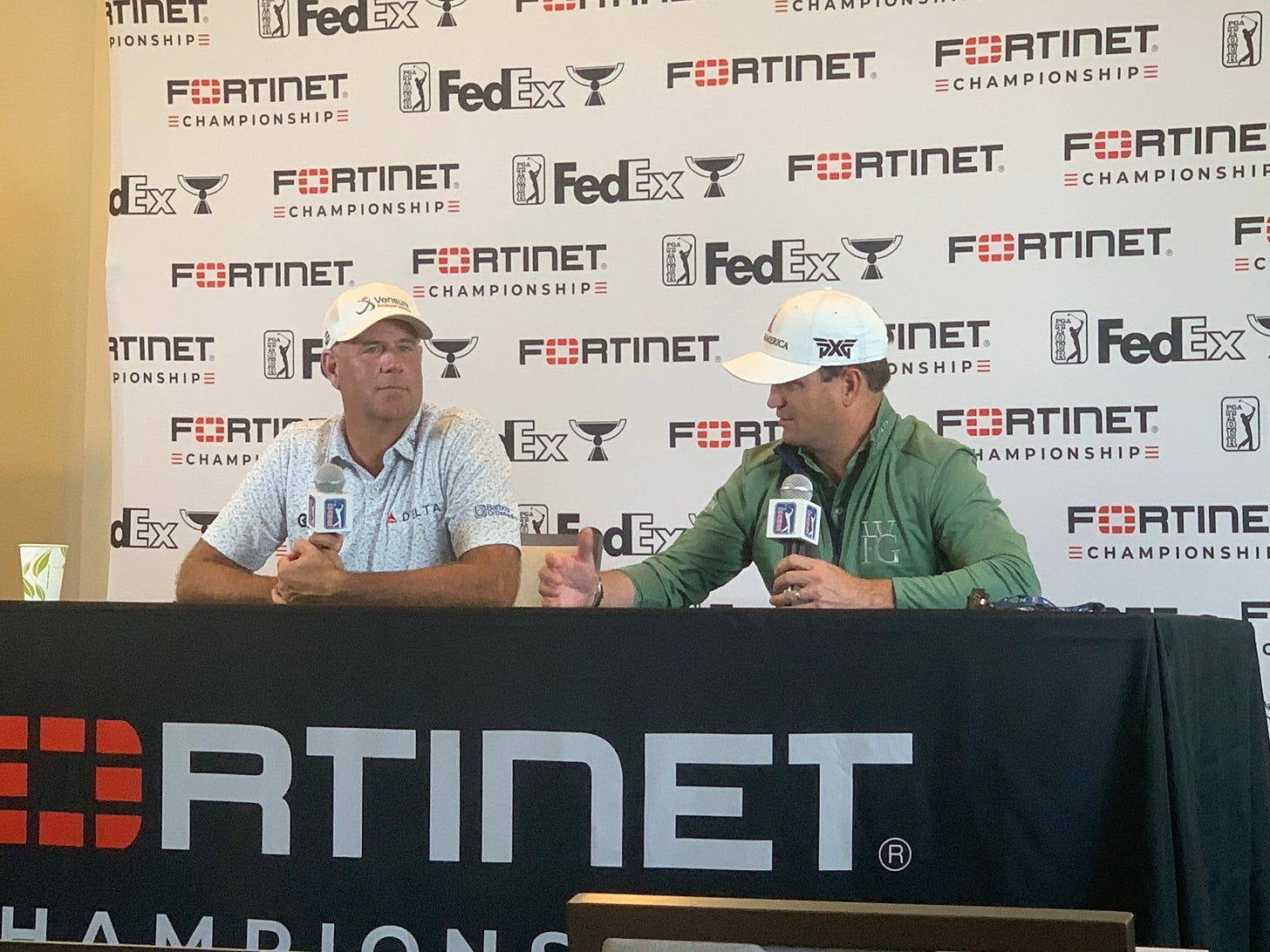

For Zach Johnson, the Ryder Cup captain, playing the Fortinet Championship in Napa is a brief respite before the pressures of attempting a United States win on European soil for the first time in 30 years. “I hope they both win,” Johnson said of Homa and Thomas this week, “and we tie for third,” Johnson said of himself and assistant captain Stewart Cink, also in the Napa field.

Their motives for making the Northern California trek, along with the wine and food, are clear, and provide this first event of the reimagined Fall Season with unique intrigue. And motives for the PGA of America coming to Napa in the first place, 55 years ago, shed light on the perpetual fragility of professional golf and the pivotal role this tournament once played in its formation.

In the late 1960s, much like today, players’ patience had worn thin with professional tournament golf. Club professionals, who then held veto power over the PGA of America affairs, nixed a potential Frank Sinatra-sponsored event in Las Vegas. Talk of a player mutiny was mounting.

The Northern California swing was at an inflection point, and a big-money sponsor was needed to ensure its future. A 1964 tournament outside of Sacramento was a one-and-done flop. The San Jose event had seen its final days. Even the San Francisco stop at Harding Park struggled to appease its sponsor. Fans mostly chose to stay indoors and watch January football rather than brave the weather. Short daylight and winter weather limited suitable courses for full-field January events, so the PGA leaned heavily on Southern California courses to open the season.

By this time, Harvie Ward had built the reputation as a tremendous amateur golfer, having won the NCAA title in 1949, the British Amateur in 1952 and U.S. Amateurs in 1955 and 1956. The North Carolina native settled in San Francisco to work as a car salesman for millionaire Eddie Lowery, who at age 10 had famously caddied for Francis Ouimet in his famed 1913 U.S. Open victory. Lowery sponsored amateur golfers and, in 1956, arranged a match at Cypress Point between his two amateurs, Ward and San Franciscan Ken Venturi, and two renowned pros, Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson. The pros took the match, 1-up, in a storied display of shotmaking.

When Silverado Country Club opened in 1966, a $100 million development over 1,200 acres in Napa, Ward was hired to promote its Robert Trent Jones Jr.-designed courses. Jack Ashby, then president of the Kaiser Steel corporation famed for rapidly building WWII ships, became a Silverado member. According to reporting from Art Spander and Art Rosenbaum in The San Francisco Chronicle, tournament naming rights were negotiated between Ward, Ashby and TV executive David Sacks. Calls were made to Joe Dey, tournament director of the PGA, and Edgar Kaiser, heir to the Kaiser throne.

On August 3, 1967, on the top floor of Kaiser’s downtown Oakland headquarters, the $125,000 Kaiser International Open was announced as the largest purse for any PGA event in California. “We didn’t have anything definite,” Ward was quoted in The Chronicle regarding Silverado’s prospects of hosting a PGA tournament. “Then, when I was taking a shower, I got the idea to contact Kaiser. It worked out fine. And,” he laughed, “I haven’t taken a shower since.”

The inaugural event was scheduled for January 18-21, 1968, a week after the season-opening Bing Crosby Pro-Am at Pebble Beach. Silverado drew big names such as Arnold Palmer and Lee Trevino, but Jack Nicklaus was a no-show. Kermit Zarley won the $25,000 winner’s check.

The bolstered Northern California swing didn’t quell the rifts within professional golf, however. In the fall of 1968, players unanimously defected from the PGA and formed American Professional Golfers, Inc. The future of professional tournament golf became a tug-of-war over sponsorships. “This is where the dancing girls are,” boasted APG attorney Sam Gates, in a play to lure business partners. On September 14, according to The Chronicle, Kaiser became the first sponsor to sign with APG. “We intend to have the best players in professional golf compete in our event,” said Vern F. Peake, the Kaiser tournament general chairman. Leake said he hoped the APG deal would “serve as a catalyst in settling the differences” between the APG and PGA.

Napa would follow APG’s inaugural event, the $100,000 Los Angeles Open. The PGA of America invoked its non-compete clause after hastily scheduling the Alameda County Open for the same week as the Los Angeles Open. “If a player decides to go with the other group,” PGA commissioner Max Elbin warned, “his PGA card will be lifted immediately.”

A compromise was reached at the PGA executive meeting in December. “The short, unhappy life of the American Professional Golfers has ended,” Spander wrote. A Tournament Players Division — renamed the PGA Tour in 1975 — was established. A tour council was formed, with players having veto power. APG events, including Silverado, transferred to the PGA.

Napa remained a fall event and Kaiser retained naming rights until Anheuser-Busch upped the purse to $200,000 in 1977. The tournament moved to Kingsmill Country Club in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1981. In 2010, the Frys.com Open moved to CordeValle Golf Club in San Martin, south of San Jose. In 2014, the event moved to Silverado where it has remained. Safeway became the sponsor in 2016 until Fortinet, a cybersecurity company, took over in 2021.

Spander, who began with The San Francisco Chronicle in 1965 and in 2009 earned the PGA of America Lifetime Achievement Award, greeted longtime colleagues upon entering the Silverado press room Wednesday afternoon. The reporter, who has covered 50 Masters tournaments and Rose Bowls each, is a staple here and took the microphone to ask Thomas about his struggles.

“Was that a major concern where people kept asking you, hey, what's the matter, what's the matter?” Spander asked. Thomas, understanding the respect Spander commands in these parts, answered in kind. “Concern, no,” he said. “Don't take this the wrong way: Annoying, yes.

“All it takes is one week, one stretch, one whatever you want to call it that could just completely flip everything and nobody even talks or remembers it anymore.”

A golfer hoping Napa can cure what ails him. Just as the PGA did 55 years before.

Great article, Nick. See you next week.