Sunol Valley: The Bay Area kidnapping that launched the PGA Tour

During a 1968 revolt, PGA of America used an Alameda County tournament as leverage against defecting players. As the event drew near, two locals planned their heist of the tournament receipts.

Former Hayward Mayor John Pappas returned from the PGA tournament with his wife, Mary, shortly after midnight. In their East Bay residence the couple found two armed intruders. Their home had been cased. Mary was bound and blindfolded. John, the clubhouse manager at Sunol Valley, was ordered to collect the tournament receipts from his office safe — an unforeseen conclusion to the 1969 Alameda County Open, and six of the most contentious months in PGA Tour history.

In August 1968, players split from PGA of America events to form a rogue circuit, American Professional Golfers, Inc. Tournament golfers were tired of answering to club pros on tournament matters, and sought a larger portion of TV and tournament revenue that ballooned during the Jack Nicklaus-and-Arnold Palmer rivalry.

“This is not designed to destroy the PGA,” Nicklaus wrote in a September issue of Sports Illustrated. “Instead, we want to provide a better vehicle for the operation of professional golf tournaments. The next action rests with the PGA.”

The rogue tour swayed sponsors — “this is where the dancing girls are,” boasted APG attorney Sam Gates — and assembled a robust 1969 schedule. The APG’s first event was the historic Los Angeles Open at Rancho Park Golf Course.

“(The PGA) will continue to play tournament golf,” PGA Commissioner Max Elbin said. “It will be tough at first, but we will endure.”

Sunol Valley, located about 30 miles southeast of Oakland and touted as the first lighted championship course in the world, could host a full-field PGA event in short January daylight. In November, the Alameda County Open was announced, scheduled the same week as the APG opener.

“If a player decides to go with the other group,” Elbin warned, “his PGA card will be lifted immediately.”

Arnold Palmer, son of a longtime PGA club pro, bridged the gap between players and the PGA. Like many players, Palmer sold clubs and merchandise in PGA shops.

A compromise was reached at the PGA executive meeting in December.

“The short, unhappy life of the American Professional Golfers has ended,” wrote Art Spander in The San Francisco Chronicle.

A Tournament Players Division — renamed the PGA Tour in 1975 — was established. A tour council was formed, with players having veto power. APG events, including the Los Angeles Open, transferred to the PGA. Pending litigation was dismissed.

The first week on the player-run PGA Tour would feature two events, 400 miles apart.

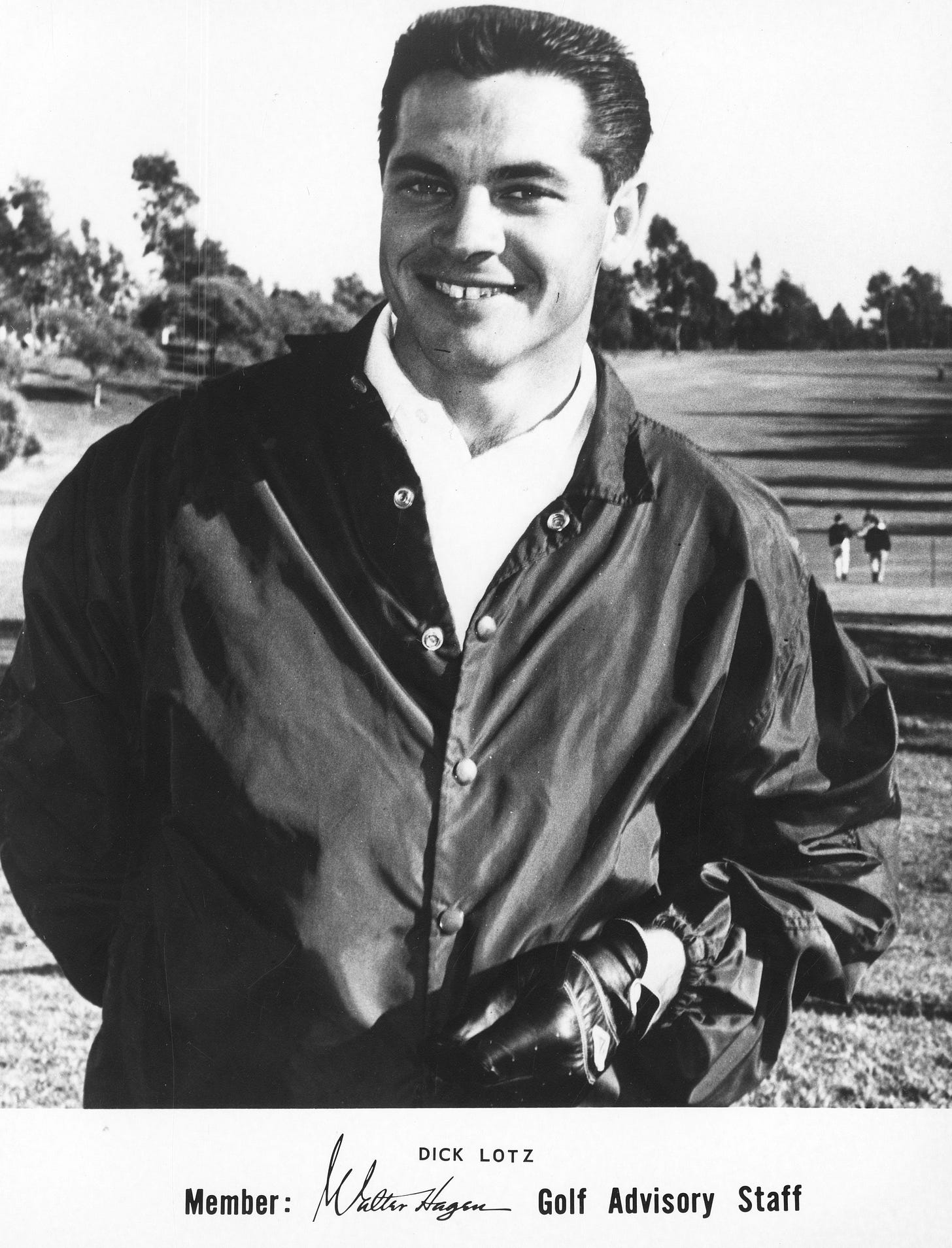

It was the PGA of America, looking to fill the Alameda County Open field with tour-caliber players. The Oakland native only held partial PGA status and was easily swayed to play 20 miles from home. “It was an easy decision for me,” said Lotz, now retired in Oakdale. “The PGA said if you play in Sunol, you get an exemption for the following week’s tournament, and the prize money you win will be official.”

Alameda pushed back Monday qualifying to accommodate LA non-qualifiers.

“As nondescript as Nixon’s cabinet,” was how Spander described the Alameda field.

During a second round delayed by frost, and with 5 p.m. sunset approaching, Sunol Valley turned on its mercury vapor lights, marking pro golf’s first night tournament. Pockets of darkness hid fairways, according to The Chronicle. Leader Bill Ogden struggled to read his yardage book because of reflection off his glasses.

Lotz had an advantage.

“It wasn’t that bad, at least for me,” he said. “I used to practice at a putting green in Alameda with lights. And I’d read the green and feel the slopes with my feet. I played a practice round or two and had a little local knowledge.”

When third-round play concluded, Lotz trailed by one stroke and $17,000 in tournament receipts sat in John Pappas’ clubhouse safe.

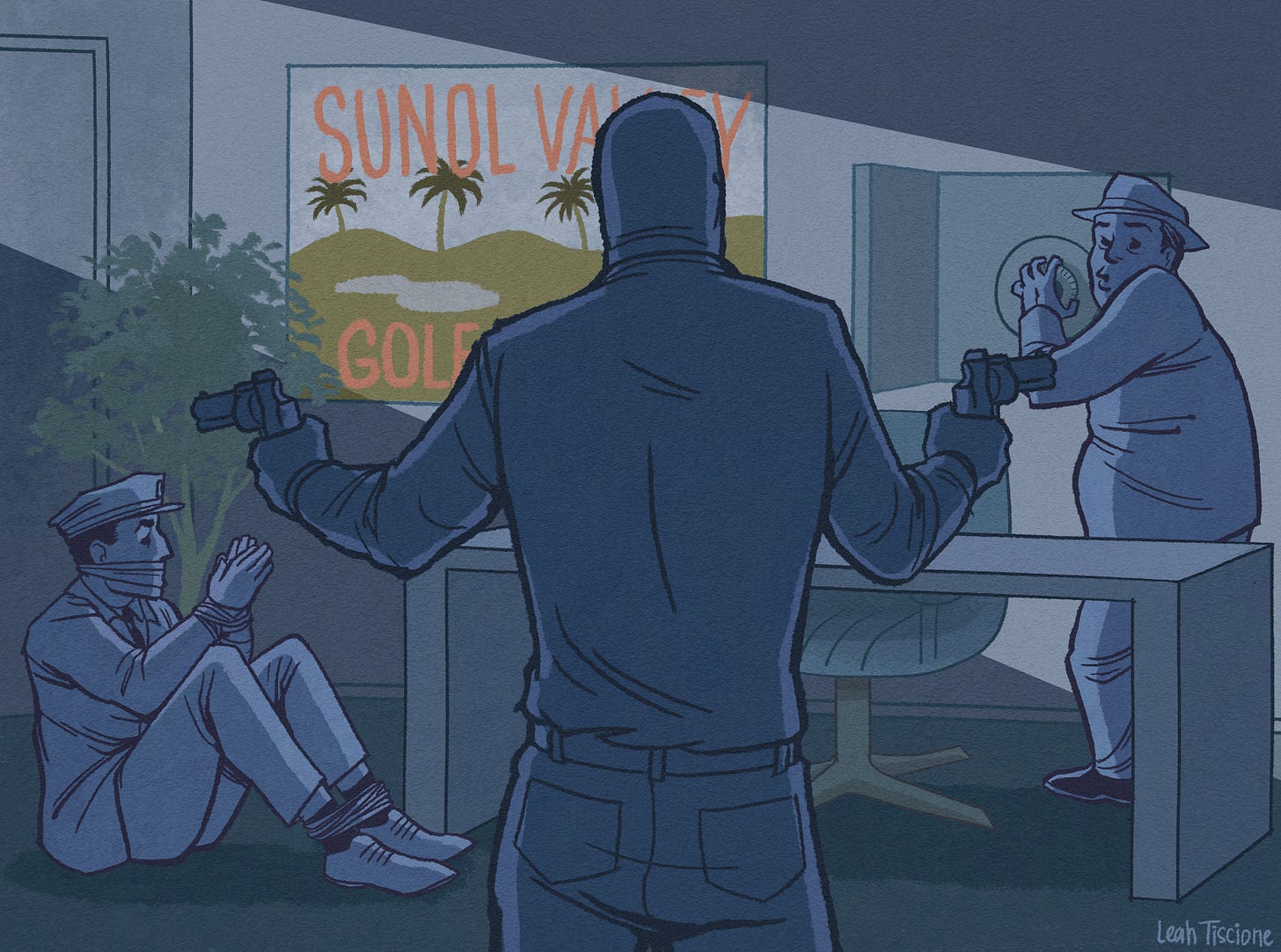

When John and Mary entered their home at 12:20 a.m. and flipped on the lights, Carl Edward Warren and Douglas Rice Spencer were in their kitchen, armed and masked.

“As I glanced around the corner of the kitchen alcove, I saw a dark figure, and as he moved to me mumbling something, I saw his gun,” John testified, as reported in the Hayward Daily Review.

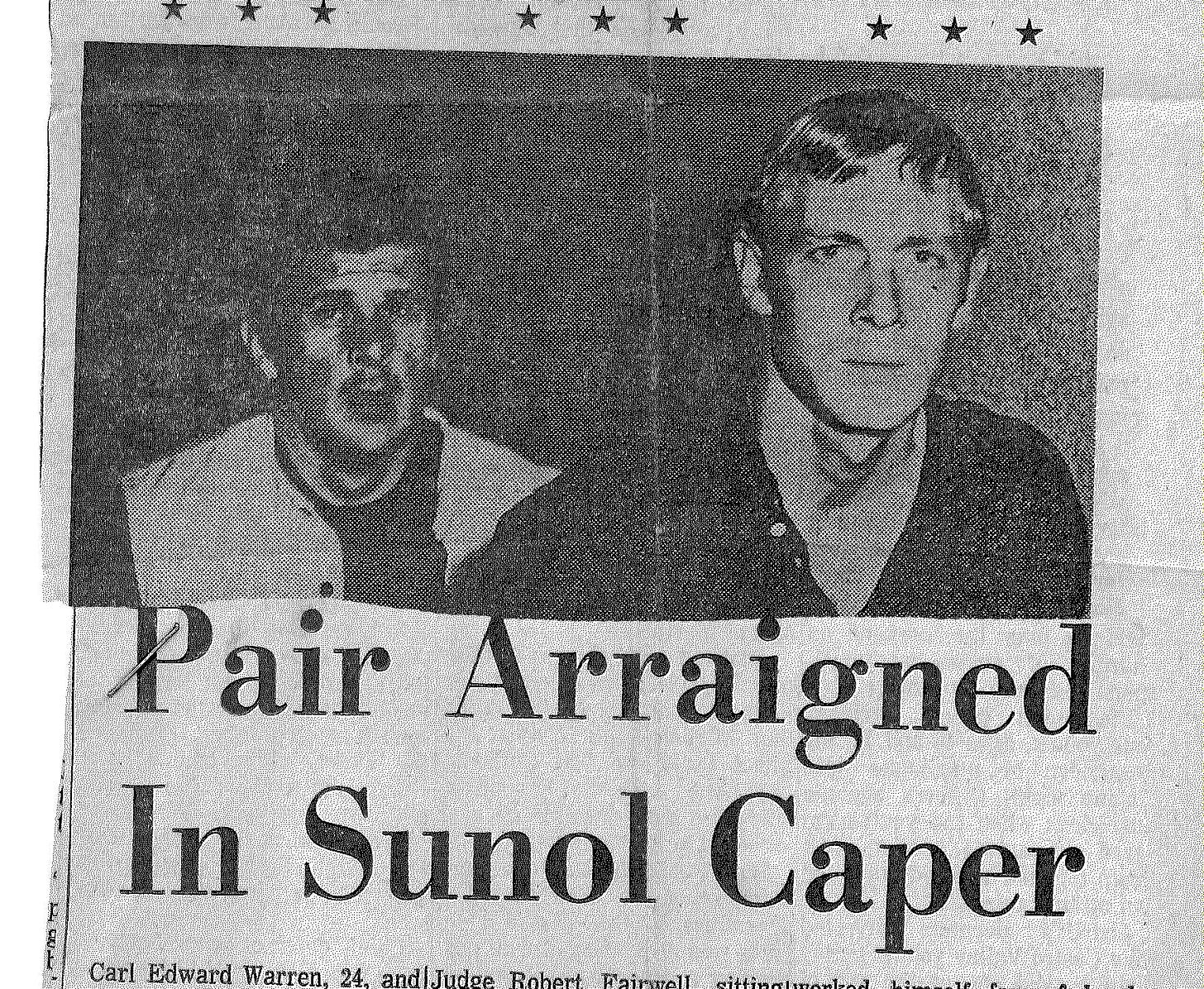

Warren, 24, and Spencer, 23, both from San Jose, wore masks and rubber gloves. John recognized Spencer as one of two men who knocked on his door weeks earlier, asking to speak with his son, Paul. The interaction was suspicious, as Paul was married and lived on his own.

“The plan was that they were going to keep Mary right here with the one fellow (Spencer) and the other fellow (Warren) and I were to go out to the club and empty the contents in the safe,” Pappas testified. “And if we didn’t get back, or if something went wrong, that would be the end of it as far as Mary was concerned, and as far as I was concerned.”

Mary’s wrists and ankles were bound. Her eyes were covered with black tape. Worried the bandits would fumble the heist, John called the Sunol Valley clubhouse. He told security guard Jimmie Lombardo that he would stop by, with a friend, to drop off a winner’s check.

“Beautiful, beautiful, I might even split half the take with you,” Warren told Pappas after the call with Lombardo.

With Warren holding him at gunpoint, Pappas drove his white Mustang the 16 miles to Sunol. They were met by Lombardo. “Good morning, Mr. Pappas,” said the security guard. Within minutes, Lombardo was stripped of his revolver and tied up on the clubhouse floor while Pappas emptied $17,000 from his office safe.

Warren told Pappas to empty his desk drawer, which had hundreds in cash. “I could have had a gun in there,” Pappas testified. Warren missed Pappas dumping much of the cash into a nearby garbage bin and didn’t have Pappas check a filing cabinet “with a lot of money in it.”

Pappas helped Warren carry the cash to his parked Mustang. He asked his captor to ensure his wife’s safety.

“He knew he was slipping by that time,” Pappas testified. The Hayward councilman dissuaded Warren from calling the home from a lit phone booth.

“I said, don’t be silly, you’re gonna have a cop come along and the first thing he’s gonna do is come into a darkened gas station and look for us,” Pappas testified, as reported in the Daily Review. “(Warren) says, ‘Yeah, you’re right. Damn it, you’re always right!’”

Mary, in her testimony, said this was when Spencer became frightened.

“He says, ‘Well, I’ve got to blow here. I can’t hang around, something’s gone wrong.’ And as I looked down my nose, I could see the barrel of the gun right there,” Mary said. “He said, ‘I’m sorry, we didn’t want anybody to get hurt, but that’s the way it is.’

“The phone rang.”

It was Warren, telling Spencer the money was secured. Pappas and Warren returned to the house around 4 a.m.

Lombardo, in this time, freed himself to call police, saying there was a prowler on the course.

When police arrived at Pappas’ home, Warren had fled in Pappas’ Mustang and Spencer in the bandits’ 1960 Pontiac convertible. Mary and John were left bound.

“It was a quiet night,” recalls officer Don Moura in a phone interview. “There was an all-points (alert) put out that an incident had occurred, and it involved mayor Pappas. A possible kidnapping.”

Moura was friends with Paul from Chabot College, and knew the Pappas’ house. He positioned his patrol car behind a nearby bowling alley, where he could see the home blocks away.

The officer recognized the white Mustang when it came down the road. It had Alameda County Open decals. The bandits’ Pontiac followed.

“The guy looks at me and I don’t recognize him as John or Paul,” Moura said of the Mustang. “I radioed, ‘Get some cover down here; I want to stop this Mustang.’”

The Pontiac turned into a gas station. Moura stayed with the Mustang. When Warren made a left, Moura turned on his lights. Warren pulled over. Moura covered the left side of the car. Officer John Pearson covered the right.

Another patrol car stopped directly in Moura’s shooting line. “Trust me, this made me nervous,” the officer said.

Warren threw his keys out the window. Moura made the arrest. He took a .357 Magnum off Warren and found a .32 automatic pistol in the car. Bags of money were strewn in the back seat.

“I went back to the patrol car and said, ‘Look, are the Pappas family OK?’” Moura recalls. “I gave him a cigarette and he told me they were OK.

“As far as I’m concerned, God was looking over all of us,” said Moura, retired outside of Sacramento. “It could have gone sideways pretty easily. He could have come out of that car shooting.”

At the gas station, Officer Pratt Truscott pulled over the “very dirty” Pontiac. He was writing down Spencer’s information when a police radio report said Warren was in custody. Truscott stopped his questioning and headed to Warren’s arrest. Spencer fled south.

Moura spent the night at the jail, counting the cash stolen from Sunol Valley. He credits Lombardo’s call to police with keeping everyone alive.

“He told them there has a prowler. Why? He knew law enforcement,” explains Moura, who became a training officer after years on the beat. “If it’s a prowler call, we come lights off. He was afraid for Mr. Pappas’ life. He knew if he said we got robbed of everything, everyone would come, and he didn’t want him shooting Pappas.”

Around noon, Lotz teed off with the final group, oblivious to the kidnapping and robbery. “I was more concerned with being exempt the next year,” the golfer said.

Most Sunol Valley spectators were in the clubhouse watching Joe Namath take on the Colts in Super Bowl III, Namath’s guarantee game. Around halftime, police caught Spencer outside Watsonville, near Monterey. Detectives testified they found a gun, hunting knife and rubber gloves in Spencer’s possession.

At the Los Angeles Open, Charlie Sifford and Allan Henning were headed to a playoff, one shot ahead of Billy Casper and eight of Palmer. Sifford, the pioneering Black pro, birdied the first playoff hole for his second PGA victory.

Lotz was making the turn, tied for the lead, as Namath and the Jets celebrated their improbable upset. Spectators returned to the fairways.

Lotz made a long putt on 17 to retain a one-shot lead, then tapped in for par for his maiden PGA win. He credits a caddie he calls Buster for steadying his nerves. Older brother John finished tied for eighth, six shots back.

Three months later, Warren and Spencer were sentenced five years to life on first-degree robbery, kidnapping and burglary charges.

The PGA reimbursed Sunol Valley for its tournament losses, according to The Chronicle. The 1969 Alameda County Open was the last PGA Tour event held at the course.

Sunol Valley owner Frank Ivaldi fell behind on his lease with the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. By 1972, the PUC was investigating the course’s bookkeeping amid suspicion of skimming profit. Ivaldi owed more than $300,000 in back rent by 1974, then sold his lease to East Coast mobster Tony Romano.

The deal embroiled the PUC. A 45-page grand jury report, which listened to 40 witnesses, questioned San Francisco Mayor Joseph Alioto’s role in the sale and called for the firing of three officials. During a disputed meeting in Lake County, Romano claimed Alioto assured him there would be no problem with the sale. Eventually, Ivaldi regained the lease.

Sunol Valley closed in 2016.

The course entrance is now guarded with barbed wire, a swinging gate and “No Trespassing” signs. Ahead sits the dilapidated clubhouse. Worn golf balls litter the property.

The public utilities commission has surveyed residents on the property.

“The list of potential uses is not exhaustive,” reads the survey. “Proposers may submit proposals for any legal uses, except for golf course, marijuana cultivation, and quarry uses.”

Nick Lozito is a freelance writer. Follow him on Twitter at @NickHLozito or contact by email at nlozito2@gmail.com.